SCREW IT!

Graphic Reasons Why

Screws Shouldn't be Used to Fasten Boat Parts

by David Pascoe, Marine Surveyor

Here's yet another good reason why, when you spend a lot of your hard-earned money for a boat, you shouldn't automatically assume that the builder knew what he was doing when he built the boat.

Contents

CaseDecks That Don't Fit

Signs of Mismatched Hull and Deck Shells

with 4 photos and 1 illustration

Case

The photographs below illustrate some design and construction errors that violate some very fundamental rules. One would think that after 40 years of fiberglass boat building, virtually all builders would know that you do not use screws to fasten parts of the hull together, or even attach hardware to the vessel. Obviously, the Australian builder of this $400,000 boat either did not know that, or did not care, for this builder used screws to attach just about everything together on this boat.

Why not use screws? In a word, "glass." Even a mechanical idiot wouldn't attempt to drill a hole in a plate of glass and put a screw in it, yet the primary constituent of "fiberglass" is just that: glass. And when you run a threaded screw into glass reinforced plastic, the glass shatters right along with the plastic. Thus, screw attachments into FRP are extremely weak, as the problems with this boat clearly demonstrates.

In this case, the builder used screws to attach the deck to the hull of this forty footer. It is true that he did glass over the hull/deck joint on the inside, but that didn't help much because he then ran the screws for the rub rail right through the hull. That resulted in water leaks at every screw hole as shown in photo at bottom of page. But that was only part of the problem. Since the deck did not fit the hull very well, there was a nearly one inch overlap at the stern as shown in photos below. The builder simply filled the gap with putty which later fell out, leaving the large gap.

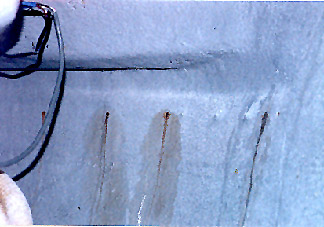

Subject vessel with stern rub rail removed.

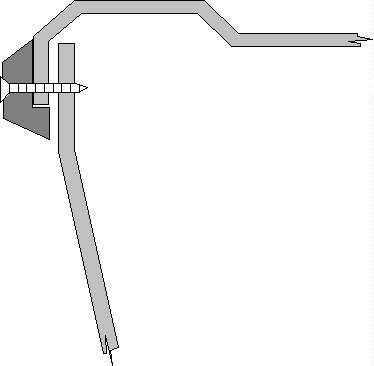

Illustration showing how a typical hull/deck lap joint is put together with screws. In this case, the improper fit of the deck leaves a large gap between the two parts, making the joint even weaker than it normally would be.

Since this occurred at the stern only one foot above the water line, wave action caused water to enter the gap which eventually worked its way into the hull core. But this is only the beginning of the owner's problems. A large, wrap-around windshield was attached to a balsa cored deck with screws, most of which had pulled loose. Further evaluation showed that a lot of other hardware was also attached by screws. The owner began to suspect a problem when leaks in the overhead developed down below. This lead to the discovery that it was the windshield screws that were leaking into the balsa cored deck. Then the owner hired a surveyor to check out the rest of the boat. This led to the discovery of the water saturated hull core and cracks in stringers, frames and bulkheads.

Several months of trying to get the builder to take the boat back have resulted in consistent denials by the builder that most of these problems are real. In the meantime, the owner is faced with the prospect of an international lawsuit.

Decks That Don't Fit

You can see the kind of problems that develop when a deck shell doesn't exactly. Somehow the mismatched parts have to be pulled together. But to simply force them together puts a stressing load on the fasteners and the parts being forced. This can later result in either the fasteners letting go or stress cracks developing. And surely when the boat bumps against a dock, the impact will likely cause the whole thing to break apart.

Close up view of the mismatched deck joint.

The gap is seen to be nearly one inch. The builder's solution was to pack the gap full of putty that later fill out.

What the builder should have done is to at least mitre the oversize part to adjust the fit and then relaminate the area. Apparently that was too much work; better to just pass the problem onto the buyer. Bearing in mind that the molds will turn out identical parts, to solve the problem it is necessary to correct the error in the mold. That makes for a lot of costly work, so a lot of builders solve the problem by just ignoring it, turning out one defective boat after another.

Unfortunately, mismatched hull and deck shells is a fairly common

occurrence. The problems that it causes typically only begin to manifest

themselves after several years or more. The first signs are stress cracking

along the toe rail, or whatever area the excessive gap exists that was forced

together. Other signs are internal leakage and guard rails that loosen for no

apparent reason. Often we will find the guard rail molding screws backing out.

If the deck is screwed on, over the years these fasteners will progressively

loosen all around the hull until most of the entire deck becomes loose, at

which point we find guard rails loose all over. I vividly recall one Wellcraft

30' Scarab Sport that I surveyed on which the entire deck had come loose.

Every screw holding the hull to the deck had pulled loose.

Here's the result on the interior:

Water leaking into the hull around every screw.

To make matters worse, the hull is cored and water got into the core.

Signs of Mismatched Hull and Deck Shells

When looking at new boats, this condition is fairly easy to spot if you know what to look for. Simple sight down the hull sides looking for any signs of buckling or unevenness. On power boats, this will usually be evident at the stern; a dimple will appear in the hull side for decks that are too small, thus it pinches the hull when forced in place. For oversize decks, locating an excessive overlap is a little more difficult, especially if its covered up with an angled rub molding. Walk all the way around the boat, sighting upward and looking for a gap. It may be one that is filled in with some sort of caulking and even painted over.

Another thing we can do is to test all the rub rail fasteners with a screwdriver. If the screws spin, then we know for sure that the fasteners aren't holding.

For sail boats this is somewhat less of a problem, occurring mostly with smaller boats. It is not a problem at all with decks that sit on an inward flange, e.g. a hull flange that angles inward, on which the deck sits flat and makes a horizontal lap. The problem occurs on those with an outboard, vertical lap joint where the screws or bolts are run in horizontally. In this case, the excessive overlap is likely to be at the stern, although it can occur anywhere. Stress cracks along the joint and interior leaking are likely to be the first signs of a problem.

Related Article: Hull Design Defects Part IHull

Design Defects Part II

First posted on October 20, 1997 at David Pascoe's

site: www.yachtsurvey.com.

Page design changed for this site.

Last reviewed 11/28/98

Power Boat Books

Mid Size Power Boats

Mid Size Power Boats A Guide for Discriminating Buyers

Focuses exclusively cruiser class generally 30-55 feet

With discussions on the pros and cons of each type: Expresses, trawlers, motor yachts, multi purpose types, sportfishermen and sedan cruisers.

Selecting and Evaluating New and Used Boats

Dedicated for offshore outboard boats

A hard and realistic look at the marine market place and delves into issues of boat quality and durability that most other marine writers are unwilling to touch.

2nd Edition

The Art of Pre-Purchase Survey The very first of its kind, this book provides the essentials that every novice needs to know, as well as a wealth of esoteric details.

Pleasure crafts investigations to court testimony The first and only book of its kind on the subject of investigating pleasure craft casualties and other issues.