Avoiding the Blister Blues

Good Detection and Communication Techniques

Critical to Avoiding Complaints

by David H. Pascoe, Marine Surveyor

Hull blistering is a problem that has been with us for a quarter-century. One might think that over a period of twenty-five years this problem would have long since been solved, and no longer be much of a problem for surveyors. Unfortunately, our research reveals that the blistering of boat bottoms continues to be a growing source of complaints and lawsuits against surveyors. It seems to be one of those pernicious problems that just won't go away. In fact, the number of lawsuits against surveyors has actually increased dramatically in the last several years.

One of the reasons for the increasing numbers of complaints is clearly the result of both yards and independent contractors having stepped up their efforts in marketing blister repair solutions. Blister repair has become a big business and repairers are roaming around boat yards looking for blistered boats, seeking repair work. That can mean that if the surveyor doesn't find the blisters on a hull, these people probably will.

- A Problem With a Solution

- The Genesis of Trouble

- Obligation to Inform Economic Impact

- The Working Environment

- How Blisters are Concealed

- Sighting

- Weepholes and Deposits

- Sounding

- Destructive Probing

- Lamination Problems

- Describing Blistering

- Use a Camera

- Reporting

- Interpretation

- Communications

- Keep Good Records

Contents

Despite the numerous studies, research reports

and magazine articles on the subject, there is not much

concordance on the cause and effect of blistering. Most

of the literature seems directed at repair solutions rather

than how to prevent blisters from occurring in the first

place.

The simple fact is that hull blistering is caused by the

use of inferior materials and shoddy layup. As Lee Dana,

former head of engineering at Bertram Yachts told the audience

at the annual conference of the National Association of

Marine Surveyors in 1985, hulls built with high quality

resins don't blister. If builders want to build hulls that

don't blister, all they have to do is "spend another

ten dollars per gallon for resin," he said

This fact is well known, but rarely considered by surveyors

or the boating public. If boat builders wish to build hulls

with inferior resins, then they, not surveyors, should be

the ones who pay the price with warranty complaints and

law suits. Unfortunately, most complaints and lawsuits against

surveyors occur with older vessels which are either out

of warranty or the builder is no longer in business. Moreover,

most warranties only warrant the first vessel owner, leaving

the next buyer in the lurch, which explains why the surveyor

ends up in a particularly vulnerable position.

The good news is that there are a number of things that

surveyors can do to protect themselves. And, if you're not

already doing them, this article offers some highly effective

methods for protecting yourself against problems that rightfully

belong to the boat builder.

The Genesis of Trouble

My review of nearly a dozen complaints against

surveyors shows that nearly all of them got into trouble

because they (1) failed to locate existing blisters, or

(2) failed to give adequate advice to the client. Most allege

that the surveyor either did not inform the client of the

presence of blisters at all, or that he merely mentioned

their existence, but downplayed their significance.

In at least three cases, the client maintained that blisters

got substantially worse shortly after the survey was conducted,

a claim which is dubious at best. In one case, a client

claimed that blisters appeared on an older vessel a year

after a survey revealed that there were no blisters, the

so-called "mystery blister syndrome." In another,

it was claimed that blisters appeared only a few months

later.

Frankly, it is hard to put much stock in the mystery blister

syndrome. Although its well known that blisters will change

their profile considerably as a result of changing environmental

conditions such as temperature, humidity and drying out

after being hauled for a period of time, I've yet to see

a case of deflated blisters that wasn't readily observable

under proper conditions. Nor have I heard of any documented

cases where blisters developed rapidly (The lone exception

to this was Hatteras yachts which was known at one time

to have used a grossly inferior gelcoat because they painted

their hulls). The minimum development time in new vessels

seems to be around three years but usually much longer.

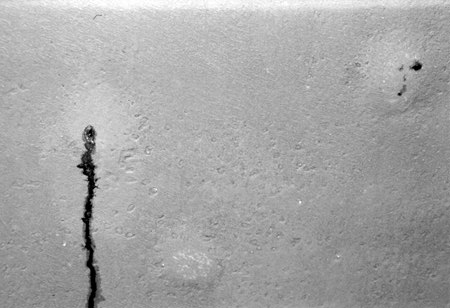

There are three blisters appearing in this photo of a boat bottom which is very clean and smooth. Two of them are easily revealed by the fluids that leaked out after the boat was sitting for many weeks. But the blister at lower center is barely visible. All of these blisters were highlighted by good artificial lighting used to take the photo.

Without that lighting, and absent the weeping, it would have been very difficult to locate these blisters. After wetting down with water, they became much easier to see. If the bottom were dirty, its not likely that they would have been located.

One way or another, unless they don't mind

footing the bill for what should be a boat builder's problem,

surveyors need to take some well defined steps to protect

themselves from becoming convenient targets for recovery

of repair costs.

Obligation to Inform

The failure to properly advise or inform a

client can certainly be construed as malfeasance or negligence.

This means that the surveyor is charged with the responsibility

of making every reasonable effort to determine the presence

of blisters, be they inflated or deflated, and advise the

client accordingly. This does not mean, however, that under

the definition of a survey, surveyors are charged with making

a technical analysis of cause and effect. It does mean that

they have duty to report on conditions that are discoverable

or apparent to any other surveyor or expert who would be

likely to find such conditions.

Economic Impact

Regardless of the prevailing wisdom of the effects of blisters, whether they cause structural damage or not, it is well known that blisters are likely to cause an economic loss to the client, for which the surveyor can be held liable in the event that he fails to detect and advise. Yet a client may exhibity no concern for the existence of blisters, nor be interested in repairing them. The problem usually arises when the client goes to sell the boat. The new buyer may demand that the your former client reduce his price by $6,000 to allow for blister repair. Or he may be approached by a hungry yard manager or repair outfit and given a litany of horrors on how blisters are destroying his boat. Either way, this is how a formerly unconcerned client can suddenly become a hostile adversary.

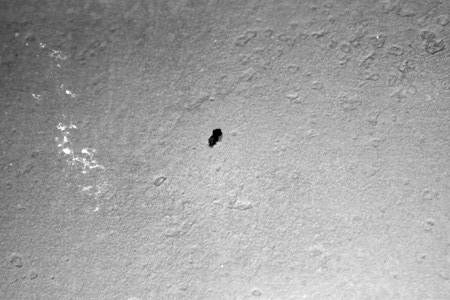

Without the dark weephole to announce its presence, this blister is not visible under ordinary conditions. It has very little raised contour and is only slightly revealed by a stong light played across it at a low angle. Yet tapping it with a coin clearly reveals the separation of the gelcoat by sound.

Many surveyors get in trouble because they

encounter conditions that inhibit their ability to perform

their work. For the most part, surveyors get so conditioned

to working under extremely poor conditions that they no

longer are even aware of how badly their work is hampered

by a poor work environment.

We should first understand that courts rarely award judgments

to plaintiffs for conditions that are entirely beyond the

control of the defendant. They award judgments simply because

the defendant failed to properly advise the client about

what he could, or could not do. It is not too much for the

client to expect the surveyor to advise him of the limitations

of his service, particularly when it involves dangerous

or costly conditions. Therefore, the principle to be applied

under all such limiting conditions is to make sure that

the client is properly advised of any factor that adversely

affects the surveyor's ability to perform his function as

the client expects him to do.

Secondly, surveyors run into trouble as a result of a failure

to fully and accurately inform the client of the full import

of any negative condition, whether by omission or misconstruction

of any material fact. An example would be to say that blisters

on a boat bottom are of no significance when, in fact, they

may cost thousands to repair.

Third, surveyors also fall victim to the failure to give timely advice. As we know so well, brokers are eager

to close the sale as rapidly as possible and clients often

close a sale long before the survey report is even

written. It is not enough to merely advise him of defects

or limitations only by means of the written report. Whenever

serious and costly defects are discovered, or the surveyor

is seriously hampered in performing his work, it is imperative

that the client be advised as soon as possible. Unless the

surveyor does this, the client may have a legitimate complaint

that he suffered a loss as a result of the failure to give

timely advice.

How Blisters are Concealed

I have yet to see a case of blistering that

could not be detected by nondestructive methods, which is

not to say that there aren't conditions that disguise them.

Two of the most common hindrances are heavy paint buildup

and dirty bottoms.

Once blistering occurs, the outer skin or gel coat becomes

stretched and will never fully return to its original contour.

The "hump" may be very slight, but if you are

looking for it, you will find it. But to do so, the bottom

needs to be clean and smooth. A bottom that is dirty and

rough is not capable of giving off enough reflected light

to show up the changes in contours so that the blister is

likely to be obscured. If the bottom is not cleaned, or

is extremely rough, the surveyor cannot do his job and therefore

he must make this situation clear to the client, verbally

and in writing.

A heavy buildup of paint that has a lot of flaking yields

a very rough surface that is ideal for hiding blisters.

Even so, this does not mean that if blisters exist they

cannot be found. It just means that the surveyor has to

look very close. Wet bottoms reflect more light and will

show up blisters much better than a dull, dry bottom. You

can visually sight the bottom immediately after it is pressure

washed to take best advantage of this. Since boats that

have been out of the water for a while are reported as most

likely to have deflated blisters, get a hose and wet the

bottom. If the bottom is clean, no matter how shallow they

are, the blisters will show up if you sight it carefully.

A third factor is the positioning of the vessel at the time

of the survey. If the vessel is sitting too close to the

ground, it becomes very difficult to get a good look at

it. Another problem is when boats are hauled out inside

of covered buildings where there is an inadequate light

source. When encountering these conditions, its time to

be extra cautious. One way or another, the surveyor has

to overcome these obstacles or risk the consequences.

This is an example of severe ply separation. The peeled away ply here measures about 3 feet across. In this case the skin out mat was so dry that there was little bonding to the inner structural laminates. The whiteness clearly indicates how dry it is. This allowed the interface between the two plies to fill with water.

While this is an extreme example, incomplete bonding to lesser degrees is commonplace. To make matters worse, it was not detectable by sounding, although there was a bit of a warning sign in that the whole hull sounded somewhat "dead." These were not blisters but water filled ply separations that do not appear to have been initiated by osmotic pressure but rather enhanced by it. Scraping with a knife below the gelcoat easily revealed the dryness of the fibers.

Careful sighting is a must. To sight the bottom

in such a way as to best locate blisters, it is necessary

to view the hull from many angles. This is not difficult,

but it may mean a lot of duck-walking around so that one

can use the available light to best advantage. A casual

look at the bottom just won't do.

Weepholes and Deposits

Some gelcoats are so weak that they are unable

to sustain the buildup of pressure and the blisters rupture

either before, or after they reach a significant size. Under

these conditions, styrene fluids usually weep out of the

laminate, leaving a telltale stain or bubbling deposit as

shown in the nearby photos. The important point to bear

in mind here is that the breach in the gelcoat is also allowing

water to penetrate the laminate, so that blistering is likely

to be progressive. Since these are actually ruptured blisters,

these telltale signs should not be ignored but rather reported

as broken blisters that are just as significant as unbroken

blisters.

Sounding

Sounding a hull is an audible technique that requires a high degree of skill and finesse. We've seen surveyors attack hulls with a plastic hammer as though they were driving nails. That may turn up a severe delamination, but its not likely to reveal a small blister. Our experimentation with plastic hammers have determined that these are far from the best instruments to use to detect smaller flaws. For one thing, the impact surface is too wide. For another, plastic against plastic is not a very good combination for getting the best audible result. Blisters are most responsive to a small piece of metal, preferably steel, about the size of a silver dollar. Very light tapping with an instrument of this sort will do a much better job of audibly revealing differences in laminate thickness, particularly blisters.

Notice on this hull how the blisters run along a band about one foot below the waterline. Also note how they appear in clusters lower down on the bottom, and that some areas between clusters are not affected. Examples like these prove once and for all that blistering is not merely a function of material, but also a matter of the quality of the layup.

On this boat, the areas of blistering are not random but area-specific and directly related to permeability of the laminate due to imperfections. Once again, the skin out mat was found to be poorly saturated. Lower photo contrasts the dry mat against the fully wetted out structural laminate.

Should the surveyor break open, probe or scrape

blisters? Certainly it's useful to determine whether the

underlying plastic has dissolved or whether there are substantial

ply separations. But doing this falls in the category of

destructive testing. Complaints have been made against surveyors

who have gone too far in doing this. it's best to get the

owner's permission before proceeding.

Because secondary bonding failures have been identified

with large blisters, the surveyor can take one of two approaches.

If he does not, or cannot engage in destructive testing,

he can simply warn the client of the possible implications.

However, if he breaks the surface at all, at that point

he needs to go all the way. Sliding a short, very thin blade

such as a cheap steak knife or pallet knife into the blister

and probing the circumference for ply separation will usually

do the trick. If you can continue to force the blade under

the skin out mat beyond the circumference of the blister,

there is definitely a bonding problem.

On the other hand, if you cannot force it, that does not

necessarily mean that there is not a secondary bonding problem.

It could not exist at one location but appear in others.

And since this cannot be done for all the blisters, this

test can only be used to confirm positive results.

Lamination Problems

Boats that display extreme numbers of, or

numerous and very large blisters may be suffering from more

than just water permeation through the surface coating.

My studies of hundreds of blistered boats reveals that many

boats that display very large blisters are also suffering

from secondary bonding failures. Bonding failures that result

in blisters usually occur between the gelcoat and skinout

mat, or the skinout mat and the first layer of structural

fabric, usually roving. The failure to bond can be due to

environmental conditions (temperature and humidity), contamination,

or excessive delay in the layup process. Whatever the cause,

the result is an incomplete bond that provides and ideal

environment for very large blisters to develop. When a vessel

has numerous large blisters, secondary bonding problems

should be suspect. For a more complete discussion of bonding

failures, see article titled The Wonderful World of Blistering on this site.

If the bonding of laminate is weak, you may be able to separate

the skinout mat for very long distances, in which case you've

got a serious bonding problem that no commonly accepted

method of blister repair will solve. To remedy the situation,

all of the loose laminate will have to be stripped off.

Describing Blistering

It is important that the general parameters

of blistering be adequately described. One way to describe

blistering is to again use a grid and literally measure

and count the number of blisters. Using a tic-tac-toe grid

of one foot squares will yield nine squares that make it

quite easy to count the number of blisters per square foot.

Since blisters do not always show up evenly over the bottom

surface , but can appear in clusters or bands, it

is probably best not to attempt to give an exact count,

but rather to determine the density and state the condition

in terms of maximum density, but not attempt to indicate

specific sizes or locations. Attempting to describe

the size of the area and specific density can be difficult

and dangerous. This way, if the blistering spreads rapidly

to other areas , the surveyor won't get caught short.

In other words, it's better to overstate than understate.

Use a Camera

If you're not carrying a camera and using

it, you're missing out on a better insurance policy that

you could ever purchase. Good photographs will stop most

misinformed complaints dead in their tracks. Using a piece

of chalk, write the boat name and date on the area to be

photographed, and then snap a couple shots from a variety

of angles.

If you are not expert at using a camera, then you need to

practice until you become so. Bad photos won't help you

much. Take multiple shots using different angles and lighting

and learn which techniques work best. Use a flash in virtually

all conditions except direct sunlight, especially when a

subject is half-in, half-out of direct sun. Make sure your

flash is illuminating the subject. With good quality modern

cameras, auto exposures will work perfectly; there's no

need to play with timing and f-stops anymore. But I would

suggest avoiding using autofocus which does not always work

well. Get in the habit of focusing manually.

Photos won't do you any good when, several years later you

can't find them. Storing them in a file is not a good idea

because they often fall out and get lost. I store photos

and negatives in the lab's original envelope and then file

them chronologically in shoe boxes, which are then labeled

with the year. This makes for a very convenient method of

locating them quickly.

Reporting

One good approach is to develop a more or

less standard statement dealing with the issues of blisters

for every report on fiberglass boats, one which is modified

to fit individual circumstances. A good statement is one

which first informs the client that reinforced plastics

are known to be unstable. It should state that the surveyor

is not able to determine the nature of the plastics and

reinforcements of which the hull is made, and therefore

he cannot guarantee the stability or the performance of

the laminate.

To make assumptions about a laminate is to take risks that

we ought not take. To look at a hull and say, "Ah,

fiberglass," is making an assumption that is not based

on anything we really know. In truth, we have no idea of

what that hull is made of, and could be an endless array

of materials. Nor can we give any assurance of the quality

of those materials.

It should be clearly stated that warranties of the hull

are provided by the builder only, and that if there are

any questions about existing warranties, the manufacturer

should be consulted. It should go on to state that the surveyor

has made every effort to determine the presence of blisters

short of destructive testing, and that blisters were, or

were not found. This, however, does not mean that blisters

won't develop at a later date. It should be made clear that

changing conditions may result in the sudden appearance

of blisters where previously there were none. Finally, one

should point out that latent blisters, or blisters in the

very early stages of formation, or blisters which are depressurized

and deflated may also exist, and which are not detectable

by any means available to the surveyor.

When sighting the bottom, be alert for evidence of prior

blister repairs which are often done shortly before the

boat is sold. The reason for this is that the surveyor has

no idea of whether a proper repair has been made. Often

as not, and owner has just ground out the blister and filled

the void with epoxy. In this case the blistering is very

likely to continue and may come back to haunt the surveyor.

The best way to protect yourself is to report all evidence

of prior repairs and disclaim any guarantee that the blistering

will not continue.

Interpretation

Unless a surveyor is going to engage in some

serious destructive testing and analysis, he really doesn't

have any way of knowing what the presence of blisters means.

And for clients, the significance of blisters is an entirely

subjective judgment. We've seen sailboat buyers go ballistic

at the mere mention of blisters, while others may not care

in the least.

When clients question the surveyor about the significance

of blisters, the wise surveyor is one who knows that he

doesn't know, and resists the temptation to speak when he

shouldn't. In my view, the best approach is to advise the

client that only a technical analysis based on destructive

testing can answer that question, and that this is not included

in the survey service. It is best to advise the client that

a prepurchase survey is a condition and not an engineering

analysis. If you wish to get involved in destructive testing,

separate this service from the survey and set it up as a

consulting service. Start a separate file and issue a separate

report and billing, even if you end up doing it generally

at the same time. This will help protect the surveyor from

claims of a negligent survey.

Communications

Learning to communicate fully and effectively

with the client is a very good form of insurance. But there

is a fine line to be walked between communicating facts

and engaging in idle speculation. Engaging in speculative

conversation may lead the surveyor to say things he didn't

intend to say. On the other hand, several complainants told

us that they were particularly miffed by a surveyor's lack

of communication. Doctors are notorious for this and we

all know what it's like to visit a doctor with lock jaw.

We feel cheated because our desire for information wasn't

fulfilled. Our opinion of the doctor drops dramatically.

it's very easy for the surveyor to fall into the same trap

because his work is strenuous and he's usually exhausted

by the time he's finished, thereby diminishing the effectiveness

of his communication.

Obviously, the best way to communicate a blistering problem

is to physically show the client what is there. Even if

he doesn't want to, make him look at it with his own eyes.

Make it standard operating procedure to show him the entire

hull bottom. There is nothing like direct client involvement

in a problem to head off disputes.

Remember that a client who seems unconcerned about blisters

at the time he is purchasing a boat that has them, may develop

other ideas later on. If he decides to sell a short time

later, and is faced with a $6,000 repair bill, it's pretty

obvious what is likely to happen if the surveyor hasn't

adequately covered himself.

Keep Good Records

Any time a problem case ends up going to litigation,

nearly all experienced surveyors will tell you that they

often end up falling victim to a universal shortcoming -

the failure to keep good notes. Litigation usually occurs

years after the surveyor's initial involvement, and long

after his memory has faded. Thus, when a subpoena is shoved

under his nose, he retrieves his file only to find that

there's not much there to help him.

Because hull blistering is such a universal problem, any

surveyor who has been in the business long enough is eventually

going to be hit with some sort of complaint. Every one has

bad days and makes mistakes, often as a result of circumstances

beyond the surveyors control, such as being rushed or hindered

by bad weather. Sooner or later, the surveyor will find

himself caught short.

A marine surveyor can get no better liability insurance

policy than by training himself to keep good notes. Of course

it's very difficult to do that on the job when there are

so many distractions and difficulties. He can't take good

notes while standing in the rain or on the deck of a bouncing

boat. But he can train himself at every instance to review

his work once back at the office, and to fill in or expand

on those notes he did take while on the job. This is why

photography can be so useful. It only takes moments to snap

a picture of a condition that might take ten minutes to

attempt to write up on paper or, worse yet, can't be written

up at all because of adverse conditions.

We should bear in mind how lame our excuses are likely to

sound when sitting in front of a jury.

Related Article: The Wonderful World of Hull Blistering

First posted 5/19/97 at David Pascoe's site: www.yachtsurvey.com.

Page design changed for this site.Last reviewed 11/28/98

Professional Marine Surveys

- Hull Design Defects - Part I

- Hull Design Defects - Part II

- Surveying Boats With Molded Integral Grid Systems

- Surveying Wood Hulls

- Avoiding the Blister Blues

- Sinking of EL TORO II

- Storm Damaged Boats

- Insurance Surveys and Reports

Power Boat Books

Mid Size Power Boats

Mid Size Power Boats A Guide for Discriminating Buyers

Focuses exclusively cruiser class generally 30-55 feet

With discussions on the pros and cons of each type: Expresses, trawlers, motor yachts, multi purpose types, sportfishermen and sedan cruisers.

Selecting and Evaluating New and Used Boats

Dedicated for offshore outboard boats

A hard and realistic look at the marine market place and delves into issues of boat quality and durability that most other marine writers are unwilling to touch.

2nd Edition

The Art of Pre-Purchase Survey The very first of its kind, this book provides the essentials that every novice needs to know, as well as a wealth of esoteric details.

Pleasure crafts investigations to court testimony The first and only book of its kind on the subject of investigating pleasure craft casualties and other issues.